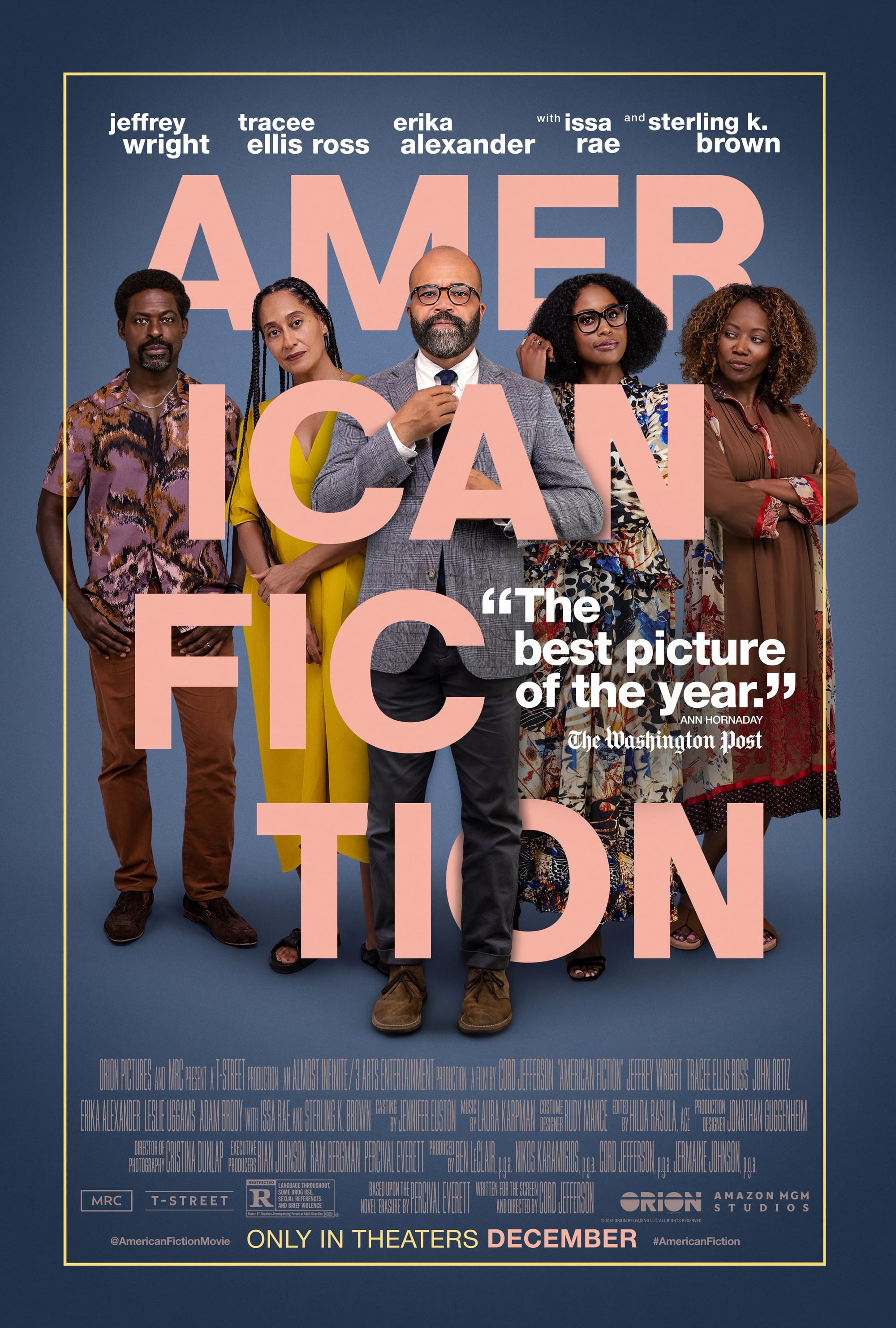

American Fiction

“There is no moral. That’s the idea.”

Swamped by professional and personal issues, Thelonious “Monk” Ellison is a frustrated novelist who's fed up with an establishment that eagerly profits from Black entertainment relying on tired and offensive tropes. To prove his point, he uses a pen name to write an outlandish “Black” book of his own, a book that propels him to the heights of critical acclaim, and straight to the heart of the hypocrisy and madness he claims to disdain.

“White people think they want the truth, but they don’t, they just want to feel absolved,” is a skeweringly true statement made in a film that examines how when White America says they want an “authentic ethnic experience,” what they mean is, they only want what to their mind is the “primitive” experience. Show me your shiny rocks! Dance! Leap about for me! Rage and scream at each other! Oh, the pathos! Oh, man’s inhumanity to man! Oh, now let’s go to brunch and discuss! It’s skewering and true, because, as a culture, White America sees themselves as inherently superior, as generally being more civilized then other cultures, both foreign and domestic. That’s why they often vacation in underdeveloped or impoverished countries, sipping drinks served by locals making pennies, they want the kind of thing that they can enjoy while slumming about on a Sunday lark in the city, as if they’re going to a zoo or perhaps a cock fight. They don’t want reality. Reality is guilt.

The anger sparked upon George Floyd’s murder by Derek Chauvin and the Minneapolis Police Department, and the events that followed in the summer of 2020, caused a part of White America to very deliberately place a lot of importance on the idea of reading Black authors who were discussing the Black plight. Based on Percival Everett’s novel Erasure, American Fiction is first-time Writer/Director (and the recent Oscar winner for Adapted Screenplay) Cord Jefferson’s attempt to unpack this world, satirizing not just White America’s voracious demand for Black stories, and the white-dominated industry that regulates this market, but also Black America’s participation in it. The film asks the question: “But at what cost?”

Monk is a largely ignored, but still, a published author, and a disillusioned college professor, one who is currently struggling to sell his latest work to a publisher. He is a bit of a prickly pear, lonely and alone, brooding, judgemental, and perhaps more than a bit unlikable, as he can sometimes be rude and condescending while keeping others at arm’s length. Of course, all of this is very much due to the well of pretty relatable personal issues he has bubbling beneath the surface.

A sudden avalanche of familial problems only make things worse.

It’s at this point that Monk happens upon a successful Black woman author whose wildly popular novel centers on the very cliched life experiences of inner city Black women. Monk believes stories like this are playing into a very toxic industry norm, and more than anything, he wants a place in the market for Black voices and art that aren’t like this, that don’t rely on such stereotypical racial experiences. Recognizing that this author’s bougie middle-class upbringing is so much like his own, he believes that her book is nothing but a fantasy cashing in on harmful tropes. And since her success is so clearly dwarfing his own, Monk does what many writers would do...

He gets drunk and passive-aggressively writes a “joke” novel under the pseudonym Stagg R. Leigh, a novel that brings in every African American inner city stereotype he can think of, and all of it supposedly written by an author who is not only an ex-con, but a wanted fugitive. His general plan is to submit the book as a big fuck you to a publishing industry hungry for the “Black experience,” but only if it’s a very specific kind of experience, and then he can stand up and go “Ha! J'accuse!”

Pure vindication.

But the publishing world loves it. They love the joke novel.

Love it. They have to have it. They offer Monk the kind of money for his book that was unheard of even in the days when literary fiction was a reliable market. There’s even interest in the movie rights from the studios. It’s a huge amount of money to suddenly fall into his lap, and all he has to do… is take it.

All of this happens to him right as his elderly mother needs to be placed in an expensive memory care housing facility for seniors who are developing Alzheimer’s, and the formerly fairly well-off matriarch is financially in dire straits. They may have to sell her beach house, and maybe even let the long-time housekeeper go. On top of that, his sister has very recently and very unexpectedly passed, throwing the role of family caretaker into disarray. His estranged brother is struggling with some major changes in his life too, after a disastrous and also very unexpected coming out to his wife. Monk himself is not only having difficulty with his professional life, but in his personal life as well. All this is now happening to a family that is still struggling with the suicide of Monk’s father years ago, a man who everyone remarks on how much he and Monk are alike. So… what if he just took the money the White people were offering for this shitty book?

How bad would that be?

Monk struggles with the whole thing, it rankles him, but it’s not like he has many options, and it’s also a lot of money, so he deals with it. But when Stagg R. Leigh’s book is suddenly poised to win a major literary award, an award Monk has never even been considered for, and is also currently part of the jury trying to decide the winner, it’s just too much to take.

He’s an artist, after all. He has talent, and a unique voice. He has something to say. Stagg R. Leigh is deliberately false nonsense. The fact that Stagg R. Leigh is revered while Thelonious Ellison is not.. really hurts. Also, the question that really nags at him is… is his own financial enrichment worth him not just being responsible for putting out the kind of crappy art that the great unwashed masses mindlessly and voraciously consume, but does he also want to be responsible for adding to, and reinforcing the already toxic expectations of society?

“I just think we should really be listening to Black voices right now,” says one very typical, obviously very well-meaning white lady artist and fellow jury member during deliberations for the prestigious literary award. It’s a moment where she and the other white jurors have just brushed aside the opinions of the two Black writers on the jury (one of whom secretly wrote the book in question), and it’s a moment that most clearly illustrates the central idea… White America is happy to hear Black voices, but only as long as they are saying the kind of thing that White America wants to hear.

Skewering. Not subtle, certainly, but skewering nonetheless.

Overall, this is a great movie. Insightful. Funny. Endearing. The literary-world jabs are wickedly barbed and on point, as are the societal ones, but really, the good stuff is the family dynamics. That’s where this film shines. The performances are warm and sincere and relatable and touching, for all their good and ill, they feel like real people going through real problems. A wedding and the following celebration that happens late in the movie is a welcome one, one that feels very much like something that the characters deserve. Yes, they all “learn a little bit about themselves… and each other,” not to mention “the importance of family.” but still, it’s good and satisfying.

And while I think that it’s fair to say that the “what can you do” kind of shrug at the end feels like a bit of a let down, it also must be admitted, however grudgingly, that it’s an accurate ending, or at least, it’s realistic. Like the song says “you take the good, you take the bad…” and the world simply is what it is, at least right now, and that world keeps on spinning, whether you agree with the rules or not.

And sometimes, you just gotta take care of you and yours…

I can’t speak on the validity or the effectiveness of the satire when it comes to the Black community, that’s not my place, a point that is also made by the previously mentioned, very typical and well-meaning white lady artist and fellow literary award jury member, when she says, with a very chipper and oblivious, “So… what are we talking about?” as she strides into the room, interupting a heated debate happening between Monk and the same Black Woman author whose book he considered fake, the same book which drove him to write his joke novel in the first place, the same joke novel that, after a long emotionally-fraught journey, led him here to this very moment, and the same Black Woman author, who also happens to be on the same literary award jury as him, who also thinks his joke novel is trash and also believes that it doesn’t deserve the literary award either, something that kind of bothers Monk a little bit, because he considers their books to be the same…

That seems like a conversation that I’m not a part of.

That said however, the companion ideas about the subjectivity of art, the validity of art, of authentic art versus marketable art, and what an artist is allowed to do in order to be able to live a life that is sustained by their art and yet still have a life that can be considered to be true to their art, is a universal one.

Does pandering matter? Does it only matter to the people who aren’t currently profiting from it? Are you limiting your art simply by trying to get as many eyes on it as possible? Is “more eyes” a worthy goal?

At what cost?

It’s a lot like how people often complain about superhero/toy movies dominating Hollywood, which is true, but what’s also true is that in 2023, those superhero/toy movies occupied nine of the ten spots on the “Top Ten Highest Domestic Box Office Grosses of the Year” list. People will say “well, the amount of money made doesn’t equate to quality,” which is true, but what’s also true is the amount of money made does show us which movies people wanted to see the most. Basically… those kinds of films dominate Hollywood because those are the films that people want to see. Is this bad? Is it bad to give people what they want? Or should you try to show them what they should want? And is that even really a thing, or are you deluding yourself rather than admitting your failure at being able to provide what people want?

Are you better than the audience, or are you actually just shit?

I feel like there’s a lot of answers to these questions, and that none of them are really all that right or wrong. It seems like something every artist would have to decide for themselves. What are you personally okay with? What are you willing to give, and what are you willing to sell? It’s a difficult thing to consider. On one hand, you’re making money, and you’re able to live and support yourself.

But on the other hand, what is your art even saying?

In the end, I think the only option you truly have as an artist is whether or not you choose to particpate, but even then, the problem with having agency is, your choices come with consequences. Not particpating maybe means not being able to do your art at all, but particpating maybe means killing that love you have for it…

And maybe that’s the film’s point… it doesn’t matter what your intent is, whether or not you’re sincere, or how authentic your voice is, when it comes to working with the institutions that commodify art, you only need to understand one thing…

And you just have to be good with that, or not.