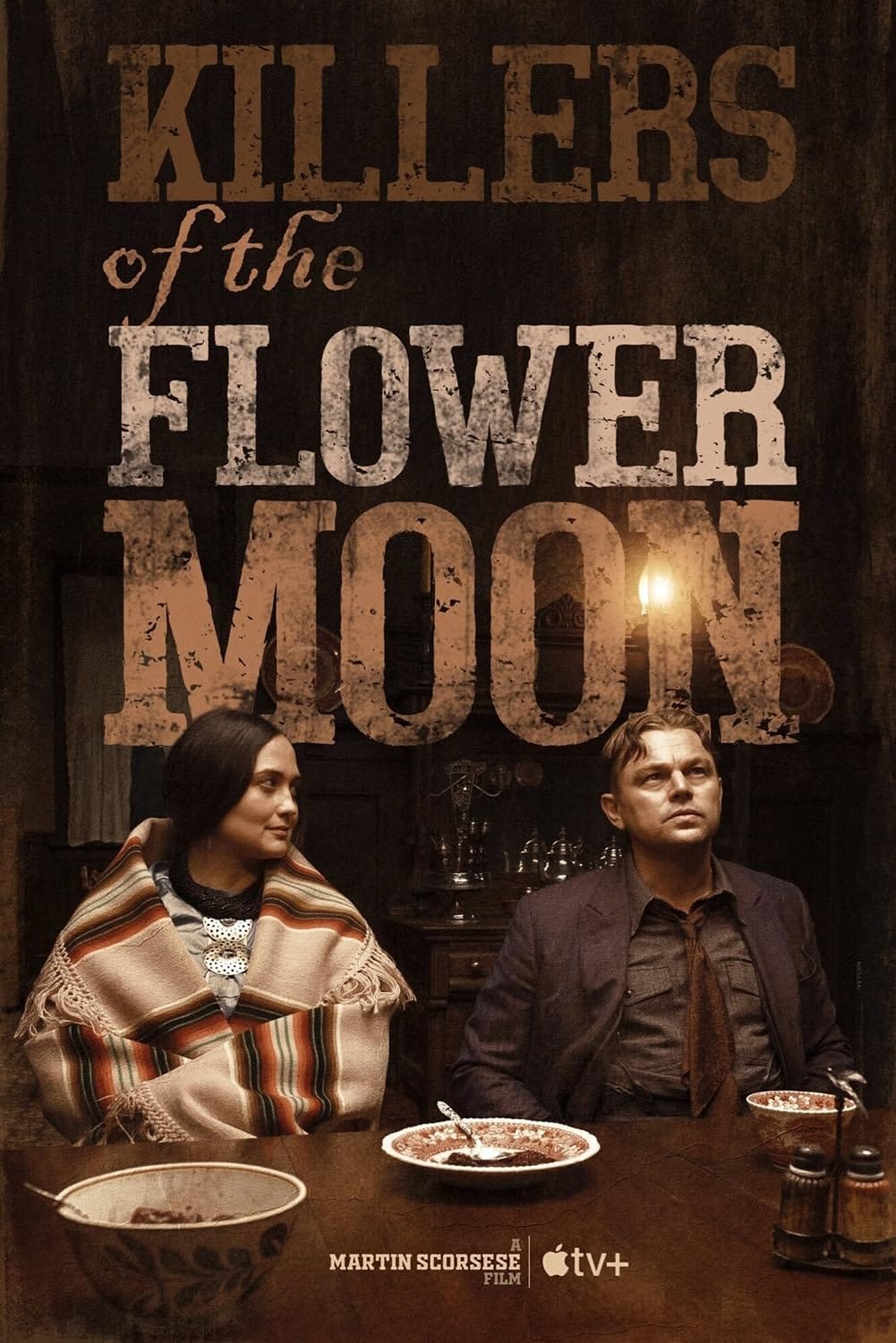

Killers of the Flower Moon

I can see the wolves in the picture…

Mollie Burkhart, a member of the Osage Nation, struggles to save her community from a spree of murders fueled by oil and greed, unaware that she shares a bed with the very instrument of her own destruction.

“Can you find the wolves in this picture?”

This is how the movie starts, paging through a children’s book.

Based on David Grann’s 2017 non-fiction book, which chronicles a series of murders of members of the Osage Nation in 1920s Oklahoma after oil was discovered on tribal land—one of the main events that led to the formation of the modern day FBI—in this story, the wolves in the picture are the white men. Some of these white men claim to be a friend of the Osage people. Other white men have married into Osage families, and have even fathered Osage children. Then, for love of oil and money, these white men murdered and destroy the people who had accepted them into their lives.

Simply put, Killers of the Flower Moon is the story of America.

It is the story of the lies, murder, and vicious colonialism of White America, of the genocide they perpetrated, all of it done in the name of greed, capitalism, entitlement, cruelty, and their bloody-minded Christian god. This is the kind of history our schools would never teach us, would refuse to teach us, because it is shameful, it is ugly, and it is inexcusable. The refusal continues today, all over this country, a deliberate effort to turn all eyes away from the truth, because how can we be the “Greatest Country on Earth” when the only tools we’ve ever used, from the very beginning, have been violent theft and murder, tools we have never once wavered from using in the many years since? How could a teacher look the next generation in the eyes and explain to them that we stem from an evil culture that has never shied away from doing harm, especially if doing that harm enriches us? How could you expect a child to keep going under the weight of that knowledge, to keep breathing in the face of such shame and complicity?

Do you look to Germany, and the generations who came after the Nazis?

No. Better to bury it. Better to look away. Better to smile and have a nice dinner, and never ever mention it again, and instead speak of other things, happy things.

That’s America.

After being pushed from their homes many times by the White Man, and finally ending up on the presumed wasteland of Oklahoma, the people of the Osage Nation found themselves suddenly awash in oil, making them the wealthiest group of people in the country per capita overnight. And much like how the smell of blood and smoke on the wind draws the attention of slavering, slat-ribbed wolves, this new world drew the covetous yellow-eyed stare of the white man, lurking, growling just beyond the edges of the firelight. Chief amongst these heartless hinds was a man named William King Hale. He was a cattle baron, a bandit, a con artist, a cheat, and a murderer, so of course, he was also a kingmaker amongst the local White people, and a false friend to the Osage.

Which is really one of the most disturbing things about Scorsese’s latest masterpiece, how unapologetically vile these white men were, how open they were about it in their own company too, and how smilingly false they were when they were amongst their victims. These were men who would kill entire families, then make commiserating noises as they dined with the survivors. These men ordered deaths like they would a second round of drinks on an Tuesday night. Absolutely savage fuckers. Heartless. Soulless. Pure monstrous evil.

Pure American.

At the start of the film, King Hale’s nephew Ernest Burkhart has just returned home to Oklahoma, with a hernia, after being a cook in WW1. Unable to do any heavy lifting, Hale puts Ernest to work as a driver for the wealthy Osage. This is how Ernest meets Mollie, an Osage woman from a large family who owns a lot of oil-rich land. Soon enough, they are married, and Mollie’s family, along with many other members of the Osage, start turning up dead, or falling ill, murdered, their wealth passing into waiting white hands.

This is a period of time that the newspapers would dub the “Reign of Terror,” a time where dozens, possibly hundreds, of the Osage Nation’s citizens were slaughtered by greedy white men hungry for oil, with little or no investigation after the fact, because white men owned the system. It would’ve gone on like this too, probably until there were no more Osage with oil-rich land left, if not for Mollie and other’s efforts to bring this to the attention of the federal government.

American history is littered with moments like this, showing the same pattern, showing the truth. Whenever a POC community prospers, White America eventually shows up to destroy it. Usually done with highway construction, often with vigilante violence that has the backing of police, if not the direct participation, and sometimes even including things like strafing runs from airplanes, it always ends the same, with the names turned into briefly mentioned footnotes, or buried and forgotten. The Trail of Tears. The Wilmington Insurrection. The Mankato Executions. The Sand Creek Massacre. The Atlanta Massacre. Rosewood. Wounded Knee. Tulsa. On and on.

The history of America is one written in the blood of massacres.

“Killers of the Flower Moon” is the story of the vicious entitlement and the red-eyed, red-toothed cruelty of a bunch of White Prairie-gangsters, one moment in rural white America’s long history of using federal programs and shady insurance claims to fund their little middle-of-nowhere dirt patch empires by the bright light of day, and violence and fire in the dead of night.

It’s not a traditional gangster picture, the kind of film most people might associate with Scorsese, but it certainly fits with the others, with the most notable difference being that where his other films could be said to glamorize the gangster, here there’s much more of a feeling of sadness, an interrogation of the soul of this country, of how this could happen, how someone could do this to another, and how it can still be so relevant to today. Through the story of Mollie and Ernest, the film isn’t just about the crime, but shows the pattern of how intrinsic injustice is to the creation of wealth and inequity in this country. It’s a commentary on how easily this violence was excused in white communities, simply because the community that was the victim of their violence, and had been for centuries, was viewed as “lesser.”

It’s a lavish production, huge and beautiful, making perfect use of the seemingly endless horizon of the state of Oklahoma. Scorsese is brilliant, as always, maybe more so here, seemingly so at ease and yet direct in his choices. The filmmakers apparently worked closely with Osage citizens to portray this ugly and deliberately-buried slice of American history, but the film has been criticized by some for centering the story on Ernest and not Mollie, who was played with such perfect nuance and such subtle complexity by Lily Gladstone. It’s a performance that got her the first best actress Oscar nomination for a Native American actor ever. It’s definitely well-deserved.

But it’s a fair criticism to ask… Why Ernest, and not Mollie?

Did Scorsese choose this because he knew White America’s sympathies towards the realities of their people’s vicious and blood-soaked history of colonialism would only extend so far, especially when it comes to women? Did he know that White Americans would be more likely to not only say to each other, “Well, she was certainly no angel herself,” but also “she should’ve known better,” and that she “was an adult who made her choice,” is that why he chose Ernest’s point of view? Is this why the film ends with a denouement on the stage of a True Crime radio-play, because Scorsese understands that White America is here to be entertained, not to empathize, not to sympathize, and certainly not to understand that this film isn’t just the story of horrific White Supremacist-driven injustice, but a story of the complicity of White America itself, that this story is meant for them to realize that through their own willful ignorance, self-delusion, and self-interest, they help to perpetuate this same kind of harm and injustice to this very day? Did he center Ernest in this story specifically because the film is not meant to be a history lesson, but an indictment of White America?

Maybe…

In the end, it’s mostly kind of shitty that, due to yet another incredibly tone-deaf example of the out-of-touch taste, bigotry, misogyny, and general dipshittery of the old wannabe/never-weres that make up the majority of the Academy Voters, people who happily admit they don’t even watch most of the nominees, when/if/should Lily Gladstone win an Oscar—which she absolutely deserves—it will be overshadowed by the controversy born out of the snubs to Greta Lee, Margot Robbie, and Greta Gerwig.

De Niro also got an incredibly well-deserved nomination, as he gives what might be one of the best performances as King Hale. It’s not a typical kind of role for him. He is riveting, as always, but small and soft-spoken. At the same time, he’s also filled with menace, portraying a man who knows he can get away with murder because he always has. Without a moment of explosive energy, De Niro demonstrates clearly that Hale is the kind of sociopath who would never stab you in the back, because he wants to look you in the eyes as he does it, but not because he wants you to know that he did it, but because he relishes seeing the pain he has caused.

The same can be said of Leo. Amazing work, although also missed by the Academy, which is too bad, because he has stepped out of his usual role here, both in speech and mannerisms, and it doesn’t feel like the typical “I’m Acting!” put on. He brings life to Ernest Burkhart, portraying him as a lunk-headed white man, one who very typically believes himself to be a good person, despite being a constant racially-motivated criminal, often going on and on about how much he “loves” his wife, and yet, at the same time, he is also the main cause of the harm in her life, both as the instigator and the direct cause. The sociopathy on display here as he takes Mollie’s family apart, not to mention her whole community, and for nothing more than oil and money, the sheer inhumanity of his duplicity, it’s staggering to see. It’s sickening. It’s shameful.

The fact that at the same time, he also portrays Ernest’s seemingly legitimate regret for “all the troubles” he has caused is brilliant, even if it is also a demonstration of the weakness in spine and spirit that is the main reason why the rest of us in this country are so fucked, doomed to go through the dark times that lay ahead because the people with direct access to the ones who are most often directly responsible for our society’s ills, don’t say or do anything with that access due to their own self-interest. They don’t want to be poorly thought of by their own community. This is something illustrated when Ernest does speak up, prompting his community to come together to implore him to rescind, to remain silent, to not to rock the boat.

It’s a scene straight out of modern day White America’s holiday gatherings.

But again, Leo’s portrayal is amazing. Absolutely amazing. Much like Lily Gladstone, it is subtle, nuanced, and complex. It is believably human, but… do I also believe that it’s accurate? No. No, I do not. Ernest is portrayed here as a dumb hayseed, a man who says he truly loves his wife, despite being the direct impetus behind the systemic destruction of her and her family. He is also portrayed as being helplessly under the sway of his uncle, King Hale. Is that possible? Sure.

But no, I don’t believe it to be accurate.

COVID and Trump has shown us many terrible things that can never be unseen, and one of those things is how willing white people are to whitewash the reputation of the monsters—their fellow white people—sitting across the dinner table from them. Do you think this is a new trend? Something that just started recently? Or could it be the real meaning of “history is written by the victors?” Is it more likely that Ernest was a poor dumb hick led astray by greed and a desire to please, despite his true love for his wife? Or is it more likely that he was a fucking monster who didn’t give a shit about anyone but himself, and this truth was just too ugly for the recorders of white history to put down for prosperity? Look around you at this country before you try to answer.

Me, I have no proof of this either way, I just live in America.

In real life, Ernest Burkhart died at the age of 94 on December 1, 1986. His will stated that he wanted to be cremated, and for his ashes to be spread around the Osage Hills, but according to stories, his son James just chucked them over a bridge instead.

Take that as you will…

Killers of the Flower Moon is an incredible film, a story of pain and sorrow, of murder and the most savage of betrayals.

It is the story of America.