Sinners

It's a real ring-a-ding-ding.

A pair of twin brothers return to their hometown in 1930s Mississippi, looking to open a juke joint and start a new life, only to realize that there is more than one kind of evil in this world, and all of it wants to spill their blood.

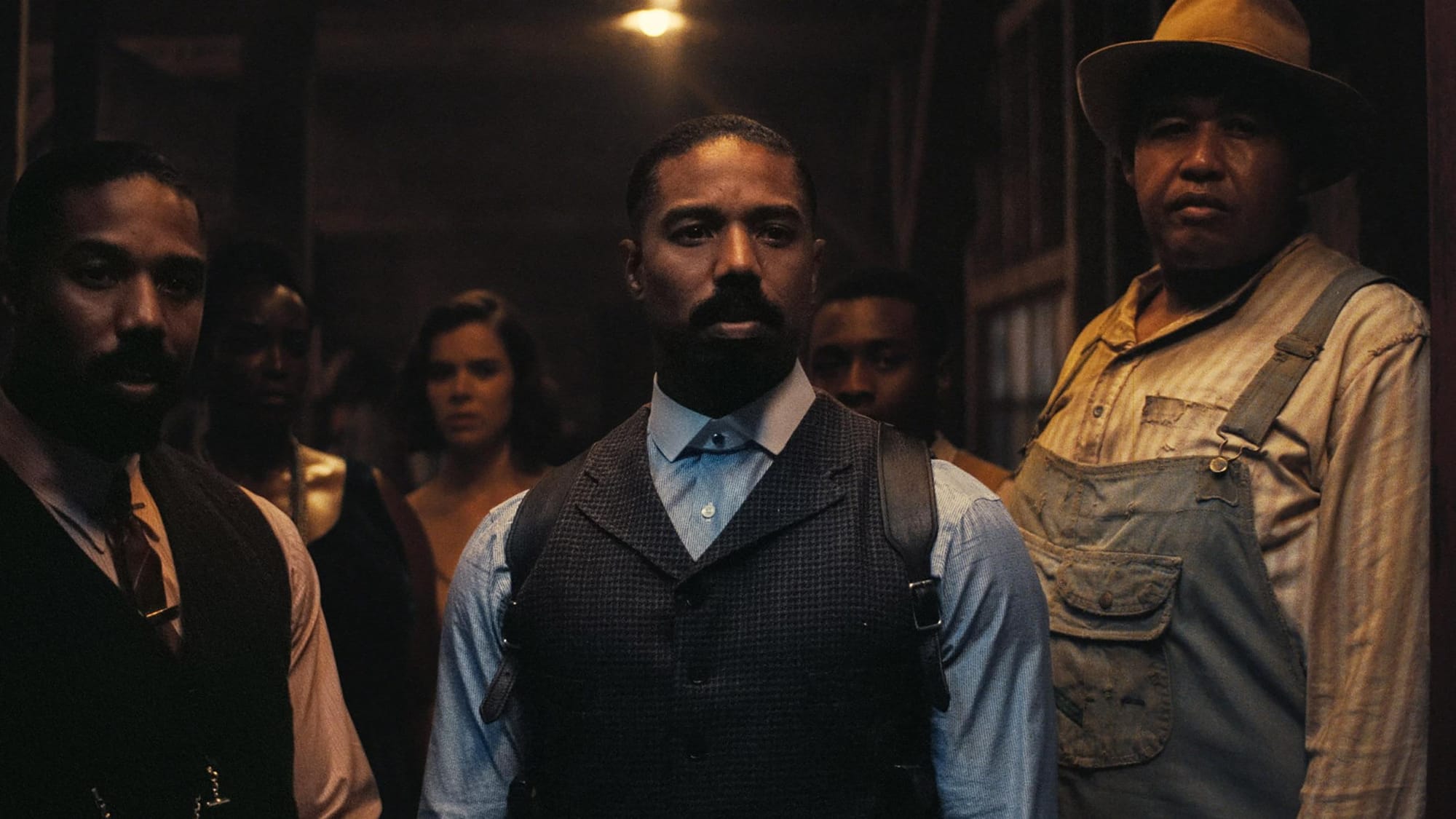

It's 1932, and Smoke and Stack Moore, known as the Smokestack Twins, after fighting in World War 1, and spending a few years up north in Chicago working for Al Capone, return home to Clarksdale, Mississippi. Flush with cash and a dream of starting a new life, it's implied that they left Chicago in a hurry, running south and vanishing in the dust, after ripping off both the Italians and the Irish.

Smoke is in blue. Stack is in red. Stack is smooth, and quick to a smile. Smoke is more taciturn, and has a more threatening air. An instinctual pair, moving as one, barely needing to check with the other, they’re more than ready to use violence if need be. They're back in town now because they've got some big ideas, so as soon as they arrive, they get to work.

The plan is to open a juke joint "for us, by us." They buy an old sawmill from a racist landowner with the fitting name of Hogwood. Then they go about building their team. First, they get their cousin Sammie, an aspiring guitarist, who joins them over the objections of his pastor father's warnings that blues music is the devil's music. After that, the twins split up, as the hour grows late, and they want to open the place that very night.

Stack and Sammie recruit the well-known drunkard and bluesman Delta Slim to perform. After letting the crowd know that there's gonna be a real ring-a-ding-ding out at the old sawmill that night, Stack runs into his white-passing ex-girlfriend Mary, who's still salty over Stack abandoning her when he left town years ago. On the way back to the sawmill, Stack, Sammie, and Delta Slim pick up Cornbread to be their bouncer, a massive, coverall-clad man working in the cotton fields.

Smoke, meanwhile, has purchased supplies and a sign from some old friends, a local Chinese shopkeeper couple, Grace and Bo Chow. Then, after laying flowers on the grave of his dead child, he manages to convince his estranged ex-wife Annie to be their cook. Annie is a Hoodoo healer, and her little shop of cures and curses is painted haint blue. She believes that the mojo bag that she gave Smoke years ago, the one he still wears around his neck, has kept him safe through all the trouble he has experienced. Smoke claims he doesn't believe in any of that, because Annie's magic didn't keep their infant daughter from dying.

During all this, an Irish vampire named Remmick, his skin blistering and smoking in the light of day, manages to take shelter in the home of a Klansman couple, just before a group of Choctaw vampire hunters show up, hot on his trail.

The Klansmen couple turn the Choctaw hunters away.

Remmick kills the ccouple.

That night, the joint is hopping. Sammie, Delta Slim, and a woman named Pearline–a married singer who Sammie is sweet on–perform on stage. Sammie's music in particular is transcendent. His voice and his guitar weaves a spell that pierces the veil, summoning spirits of Black music from the past and the future. As he sings, he is mystically accompanied by African shamans, cowry-shelled dancers, several drummers, spirits in elaborate mardi gra masks, as well as a Parliament-Funkadelic-esque electric guitarist. Soon, the dance floor is crowded not just with the juke joint patrons, but with the spirits of breakdancers, twerking women, and West Coast gangsters crip walking, and a DJ adding beats to Sammie’s song.

Delta Slim watches with a smile and says...

“With this here ritual, we heal our people, and we be free.”

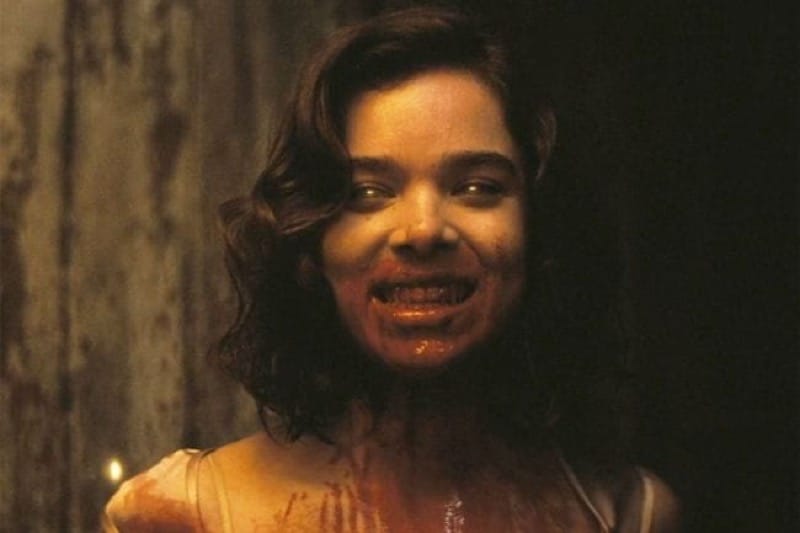

But this effusive font of Black joy eventually attracts the kind of trouble you'd expect. Like wolves at the door, Remmick and the Klansmen couple, who are now vampires too, show up and ask to be let in. Claiming that they want to join in the fun, Remmick offers money, music, and of course, love and fellowship, the usual poison apples. Stack is open to the idea, but Smoke is suspicious. He doesn't know they're vampires at this point, they're just grinning white people, which is trouble enough, so he refuses them entry. But soon after, the twins realize their patrons' use of company scrip means they aren't making the kind of cash they expected to. When Mary volunteers to see if Remmick and the other two are still around, Stack agrees. She finds the trio lurking at the far edge of the clearing, singing, being charming, offering riches, and making all of the usual vampiric innuendos.

Mary sees through their ruse a beat too late.

After that, the vampires begin to pick the unwary off one by one. Too late, Annie realizes they are beset on all sides by vampires. Smoke closes the joint early, but unfortunately, this just means more vampires, as their joint's patrons head out to their cars, or try to walk home. Finally understanding the trouble they're in, the core group arms up, and prepares to wait for the dawn.

From outside, Remmick promises to leave, but only if they send out Sammie. The vampire wants to use Sammie’s musical skills to summon the spirits of his people, the Gaellic people of the Middle Ages, who he hasn't seen in a long time. Again, he tries to tempt the others with promises of power, immortality, freedom, and riches, but when they refuse, he threatens to go attack the town, and to specifically kill the Chows' daughter Lisa. Enraged, Grace invites the vampires in for a big fight. After that, it's time for guns and wooden stakes, gleaming fangs and spilled blood, until the final tally of the Butcher’s Bill by the light of the rising sun...

After that, we jump ahead to 1992, when a famous old bluesman is visited at his club by a pair of ageless vampires, vampires the old bluesman has known since he was a boy. The old bluesman performs for them, and after declining their offer of immortality, they leave. But first, the old bluesman admits that despite how it all went down all those years ago, it was still one of the greatest days of his life. The vampires agree with the old bluesman, as it was the last time they ever saw the sun, the last time they ever truly felt free.

Sinners is a vampire survival-horror musical.

It’s a getting the band back together movie, meets a last stand type of film, pulling elements from Southern Black tradition, the Blues, old superstitions, and legends like Robert Johnson, who is said to have sold his soul to the devil to become one of history’s greatest guitarists. It’s a Jim Crow period piece about America’s pervasive legacy of racism. It’s a film about magic, religion, the power of music, the monsters out in the dark, and the need to find joy amongst all the horror. It’s an allegory for how bigotry destroys everything. And much like the works of Jordan Peele, it’s also a horror movie about the African American experience in America. Plus, it's a little bit of Demon Knight and a little bit of From Dusk til Dawn too.

It’s also an original R-rated horror movie, and the Studios were afraid the film wouldn’t be able to justify it’s nearly $100 million budget, but after 9 weeks, it has made nearly $300 million domestically, and nearly $100 million internationally, with a $48 million opening weekend, the best since Jordan Peele’s Us ($71 million) in 2019. At this point, that’s the kind of profit even Hollywood can’t deny, and they tried to too, downplaying the film’s continued success in their little pet trade rags, planting articles that talked about how, despite appearances, Sinners wasn't really all that successful, often employing the kind of passive language that most news outlets only use when a cop kills someone. In short, the Studios tried to tank the film, to push it off stage and out of the limelight. It was an effort that ultimately failed, but still, they tried, because even if they're making money off it, Sinners getting too big of a win is ultimately a big loss for the Studios.

The reason why, of course, beside racism, is because not only did Director Ryan Coogler, a two time Oscar nominee with two massively successful franchises under his belt, have a contract that gave him First Dollar Gross Points, which means he gets a percentage of every dollar made from the start, as well as Final Cut, which means he is the only who gets to say when the movie is done, the rights to the film itself will revert back to him in 25 years. This is the kind of shit that the studios live in fear of catching on with their bigger name creatives, as their expansive catalogue of films, and their sole control of those films, is a huge source of income for them. But Coogler wanted this simply because the idea of owning a film about Black ownership was meaningful to him.

And that's what I really liked about this film.

I really liked that this aspect, the idea of Black ownership, is only one part of the film. I really liked that this is a movie that discusses a myriad of topics, sometimes obviously and in your face, and other times a little more subtly, and all while still being an awesome vampire film.

Now, Remmick and the Klansmen vampires are obviously a warning about the dangers of allowing white people into spaces that are meant for people of color, as well as how the act of Black joy will always attract these white monsters looking to capitalize and exploit it, or just plain ruin it, but while the metaphor for racism is clearly apparent, there's more than that going on here.

There's also a commentary on colorism in the Black community, on who belongs, who passes, and what that default means for a person. There's also a commentary on the stranglehold White Christianity has on Black communities, illustrating how that religion originally came from a rotten hand, and is deeply entwined with white supremacy, and also how "Love and fellowship" is the preferred weapon they use to destroy, and it does it by showing that these vampires are not only familiar with the Lord's Prayer, but that they have no fear of it at all, and even embrace it. This is the film saying that Christianity is a tool of the true devil.

And the devil, in all its myriad forms, is a big part of this film, which means that the idea of the Faustian Deal plays a large part too. That shit is Remmick's bread and butter, as he often offers gold in the palm of his hand, all while smiling with a mouth full of gleaming fangs. When he shows up at the club, and asks to be let in, even playing their own music for them, all smiling and friendly, and later how he wants to get ahold of Sammi and his music, there's that deal again, just give all of yourself away, everything important, and I'll give you everything. And this is all wrapped up in a metaphor for the experience of Black artists, and the dangerous and greedy white men who then show up to exploit them. But on top of that, the film doesn't shy away from an additional commentary on the desire of POC and other marginalized communities to be a part of the white community either. The film doesn't deny the allure of all that privilege and power, nor the willingness of some to give away all that they are, just to be allowed in, and all despite that oft-proven fact that no matter what you do, you'll never truly be a part of their world, that the best you can ever hope for is to be "one of the good ones," a thrall forever beholden to their whims, their pains, their regrets, and the reprecussions of their mistakes. All of which is brilliantly illustrated once the juke joint patrons have all been turned, and are dancing and singing in the darkness, and the whole time... Remmick is in the center. This is why Annie tells Smoke to kill her if she's turned. It's because she understands that becoming a vampire means destroying yourself, that your soul, your values, the totality of who you are, your honest self, is more important than being part of a group that doesn't truly want you, and will only ever use you. Throughout the film, it's clear that, in a deal with the devil, you may get a lot promises, but in the end, you get nothing in return, and he gets everything.

On top of that, there's an interesting aspect about white people and cultural appropriation too, as whenever Remmick turns someone, he takes their thoughts and memories, their very culture and language even, as his own, stripping it of its authenticity, and rendering it as nothing more thant a false mask for him to wear, like the Coachella white girls wearing Native War Bonnets as fashion. The way the film uses this idea was not only clever in and of itself, but I also liked how the film tied this into the idea that while the film is set in the racism of the deep south, it makes clear that this isn’t a southern problem, nor is this a rural problem either, and clearly states that this is the reality of America, no matter where you go.

“Chicago ain't shit but Mississippi with tall buildings instead of plantations. That's why we came back home… rather deal with the devil we know…”

I also liked how the majority of groups that appear in this film, whether it's Black-Americans, Chinese-Americans, Choctaw, the Irish, immigrants and natives alike, are all a part of America’s legacy of racism. And I liked how the film then ties them all up into the ideas the vampires represent too, not just as outsiders who infiltrate and destroy communities from within, but also as irrevocable part of institutional racism. The drinking of blood becomes a substitute for the siphoning of financial success, of community, and ultimately, of happiness. At one point, Remmick even claims his goal is to create a new community, his bloody-mouthed pitch implying a utopian post-racial future, a “bigger tent,” one where everyone can join, but only if you first compromise, and give up everything that makes you who you are, leaving behind the things you care about. It's an offer that sure sounds an awful lot like the same offer all these Nazi-loving “big tent” white Centrist Democrats are currently demanding that everyone else accept, insisting that everyone make room for their shitty bigot friends and family members, all those pale, bloody-mouthed, happiness-sucking vampires…

And while it was a smaller part of the film, I also loved how the indigenous Choctaw were the ones who not only knew about the vampires, and how to deal with them, but they also very smartly acknowledged the reality of the limitations that come with that fight. And I loved how, when it came down to it, they gave it a fair chance, but were unwilling to sacrifice themselves for white folks who refuse to listen. It was a great metaphor for the fact that the indigenous people of America have been dealing with the problem that is white people for a long time now, and they know the score.

And then there's the whole “Just One Drop” reality of life in America.

Now, in the film, this part is directly used to highlight colorism in the Black community, but it's also used as a more lowkey way of highlighting the reality of living in white America too, as the reason why Stack abandoned Mary so long ago is, if the white people were to realize that Mary is part Black, they would consider her to be all Black, and then they'd hurt her for lying, for daring to pretend, and to reach above her station. Stack wanted her to stay away from him, to go be white, because then she would be safe. And this whole situation resonated with me as it is something I have heard my whole life too, often times exactly as it happens in the film too, from supposed friends, family members, and also strangers too, the rude and presumptious assholes who open up their very first conversation with you in this exact way...

“What are you?”

“What am I? I’m a human being.”

“I meant… more like…”

“I know what you meant.”

I was born mostly white, to mostly white people, and I was raised in a series of progressively smaller and more and more predominantly white communities. But throughout all of them, it was only ever through the lens of white culture. Nothing else, just white culture. I say this now so that you'll understand that I don't know anything else. I'm from white America, small town white America, even. This is the totality of my life experience. For the most part, the way I was raised was really no different from any other nominally Christian, cis-gendered, straight white male hailing from the whitest and the middlest areas of white middle America.

This is who I am, and this is how I see myself.

But despite the fact almost the entirety of my immediate family are otherwise predominantly a mongrel mix of central and northern Europen, and present that way, and because of the fact that my grandmother on my father's side is Japanese, born and raised in Yokohama until she married my giant swede of an american GI grandfather and moved to Iowa, where she bascially abandoned Japanese culture out of a love of American movies, baseball, and hot dogs, AND specifically due to the fact that my Japanese genetics are apparently as strong as the oft-folded steel of a katana, and as a result even the dumbest and most oblivious of white people, especially in predominantly white areas, can see it on my face...

I am considered to be Asian-American.

Now, to be fair, I'm Asian-American because I have a Japanese heritage, and like the rest of my family background, I like that aspect of where I'm from. I often joke that I am the result of Samurai and Vikings, with the implication that this should be obvious to anyone with eyes, and I can make this specific joke because it's clear that I know fuck all about any of that shit, as I am a mostly white Midwesterner. Being Japanese, or knowing anything about Japanese culture any more than any other American kid raised in the 1980s with a healthy love of ninjas, is not in any way a part of my day-to-day lived experience, or how I grew up.

I am as Japanese as the Teenage Mutant Ninja Turtles.

But because white people can kind of see it in my face, I'm Asian-American. I'm Asian-American because that's what white people say, and they're the ones who get to determine that reality, because that's what white privilege means. And they need to know this, because they really need to know what level of racism is needed when interacting with me. This category is all important to them, because the hierarchy is important to them, as is whether or not I'm "one of the good ones." And because of white privilege, because of the presumption that comes with their entitlement, if some random white person doesn't know me, they'll simply come up and casually interogate me in a way they would never do with a white stranger, saying "What are you?" and if I don't answer with "my grandmother is Japanese," then they do a guessing game. And I've found, nine times out of ten, the very first guess is always "Mexican," and I've also found that, of the white people whose first guess is always "Mexican," most of them will either say it in a way that is meant to clearly convey that they pity me and my racial handicap, or they say it like they're saying a slur, and also that they pity me and racial handicap. I've also found that once they find out I'm safely Asian-American, not long after, they will very magnanimously assure me in a commiserating tone that they don't even think of me as another race. This is very common thing for white people to say to their POC friends (ask them, if you have one...). Whether they know it or not, that is white people speak for: "Despite your obvious racial handicap, I consider you to be almost a real person," and all of this is just before they whitesplain to me how racism is actually everyone's fault, because there's n-words in all races, y'know.

In my life, where I'm from, this experience is as common as the sunrise. And much like the sun does with vampires, this experience burns away a white person's mask of being a good person, and reveals the fangs of their bigotry beneath.

And all white people go along with this too. My lived experience is that, unless they're mad because I'm pointing out the racism of white America, no white people think of me as white, even though I am, overwhelmingly. Not family, not friends, and certainly not the "What are you?" fuckholes. And if I remind them, it's akin to a squirt of bug spray on their forearm, damp and inconveinent for a bit, but then it fades away and is forgotten, at least until the next time they're bothered anew by some incessant buzzing. That this is an undeniable reality that has happened to me more times than I could ever hope to count, despite me otherwise living a fairly innocuous and accepted life amongst white people as "one of the good ones that they don't even think of as another race" for most of my life, means that I know for a fact that one thing is true, always and forever...

To white America, skin color is the only thing that matters, as that is the primary indication for them whether or not you have "pure" blood, and just one drop is all it takes to "ruin" it in their eyes.

AND THAT... is why Stack feared for Mary's safety, lest the white folks find out that she has that drop, but also... and this is the kicker that was really great about the film... as far as he and everyone else there was concerned, Mary wasn't truly black either. At best, and only to the people who knew her and her mom, she was honorary, but mostly... she was a white lady, and that meant more trouble for them then it did her, and her insistence on being there put them all in danger, and ultimately, it's what got them all killed too. That shit resonated, because that's what I tell folks, I ain't white, but I sure as shit ain't Asian either. For me, for many like me, we have a foot in two worlds, but we stand in neither. And all because the only thing that white America ever sees, first, last, and only, is the ghost of my grandmother's blood in my face.

And that's what I loved about Sinners. It's a film that is not only about the Black experience in America, it's a film about the true face of America, and how it is pale and grinning and covered in blood.

I loved that.

But even if none of that had been in the movie, I probably would've still been in, because I love vampire movies, and Sinners is a great one.

Bram Stroker's Dracula, Lost Boys, Near Dark, Let the Right One In, Blade, Blade 2, Only Lovers Left Alive, Nosferatu, 30 Days of Night, From Dusk til Dawn, A Girl Walks Home Alone at Night, The Monster Squad, The Last Voyage of the Demeter, The Last Man on Earth, Omega Man, I Am Legend, Daybreakers, the one where Alyssa Milano is naked, the various Fright Nights, John Carpenter's Vampires, Stake Land, Afflicted, Doctor Sleep, Bood Red Sky, Byzantium, Night Watch, El Conde, Abigail, What We Do In The Shadows, and of course, Buffy the Vampire Slayer, both the movie, and especially, the TV show.

They are all favorties of mine.

They're not as beloved to me as the zombies, of course. Simply put, there's an entirely different set of rules and recommendations when it comes to your initial response and your long-term fort-building in the event of a vampire apocalypse then there is in the event of a zombie apocalypse, and I personally prefer zombie apocaypse forts, but they're close enough to be cousins, so I love them both. As a result, I really liked how the vampires in Sinners were the more classic vampires types that embraced the more well-known rules.

These vampires cannot tolerate daylight. They can spend a little time in the sun, but not long. Cutting off their heads, or a wooden stake through their heart will kill them. They don't like garlic at all. It seems to be implied that silver hurts them too. It's unclear how they feel about iron or salt. I assume they have reflections. They definitely have no problem with the Lord's Prayer, so I think it's fair to assume that crosses and Holy Water don't bother them either. It didn't come up whether or not they were able to cross running water, or if they would be compelled to count every sunflower seed if a handful was scattered before them. Most importantly, these are vampires who must be invited in.

What the film adds to the mythos is the idea that the soul of the person these vampires used to be is still trapped within their bodies, and so, they are unable to move on. It seems to be implied that the feeling of desperation that results from the soul being trapped is the root of their evil. And my favorite additions in this film are the way the vampire's eyes glow in the night, some red, some silver, like an animal's eyes caught in the passing glare of a car's headlights. Also, I really loved that the vampires would drool uncontrollably just before they were about to feed. That's an absolutely monstrous and fantastic detail.

Loved it.

But while I loved this film, if I'm being honest...

It doesn’t quite work. It’s a little long, and the first half set-up feels stronger than the actual vampire confrontation and resolution. Honestly, the big end fight kind of seems to get short-shrift, with the violence seeming to be skipped past a little too quickly. And throughout the film, the question of exactly whose film this is... Sammie's or the Smokestack Twins, has a direct affect on the story's focus and how the story is told. All three are crucial to the movie, yes, but the fact that they split the film's focus so much is maybe the main reason for why the story doesn't quite come together in the end for me.

I mean, for example, I'm all for slaughtering white bigots, especially Klans men, any time a film wants to take a break and shoehorn in that scene, I'm totally cool with that, but I don’t understand why the Klansmen show up at the juke joint the next morning after everything is said and done. Sure, sure, maybe their intent was to catch the twins and the others all sleeping off the previous night's festivites, but at the same time... night riding is kind of the klan’s thing, y'know? Honestly, it feels like, if the film had the Klan show up that night, then the vampires would've taken them out, and the Twins wouldn't have been allowed the opportunity to deal with them in more traditional ways later on, which seems a little like the film was trying have their cake and eat it too, and as a result, by having the Klan show up the next morning, the whole sequence felt like an unnecessary post-script. I mean, I love watching Michael B. Jordan fire a Tommy Gun on full auto as much as the next guy, but... it felt tacked on.

Then there's Sammie‘s music. I love the idea of it reaching out through the ether and summoning up ancestral spirits of the past and future, and the metaphor for Black music being the string that connects the whole culture, but the idea that this is what attracts Remmick, because he wants to use Sammi's ability himself, so that he can see his long dead loved ones, also felt unecessary, not to mention a reach. The film seems to be aware of this too, as this particular motivation is barely even mentioned. Plus, if we want to play a little Nerd Fiction Rule Book here, if it were up to me, I'd wonder if an ability like Sammie's would even work once he's undead, that such a thing might need to be powered by a living soul. But to be fair, that's just some random nerd speculation bullshit I'm pulling out of my ass, and neither here nor there. My point is, using this as an explanation of Remmick's motivation felt superfulous, simply because... vampires feed. That's what they do, so that’s all you need. Why did the vampires show up at the Juke Joint? There's people there, and they're isolated out in the middle of nowhere.

No other explanation is needed.

I also noticed that it was the allies who really fucked everyone over. Mary, the biracial white-passing woman is the one who falls under the white vampires spell first, and is the one who first brings the vampirism into the community. And then, Grace, an Asian woman, is the one who, angry and without thinking, shoots her mouth off and invites the vampires in, and that kills a lot of people. I wasn't sure if this was an intended metaphor or not, but if not, I don't know how it was missed while making the film, because it was certainly hard not to see it while watching, and if it was intended, then it felt like it was a little underserved in its execution.

Also, in general, I'm not a big fan of the narrative decision to use a cold open shock, and then jump back in time from that moment and start telling the story. I don't see what you gain from that. Most of the time, having knowledge of what's coming, and what that means for the characters you didn't see during that first scene, just lays like an unnecessary weight across the rest of the story, distracting the audience from being present, and fully watching the film, and instead forces them to consider how what they're seeing at that moment will lead to the thing they have already seen. It just taints the delivery of everything. I think it could've been cut from the beginning and left at the end.

But that's just me, and this is one of those spilled milk things.

Finally, the nerd in me was really hoping that I'd get to see more of the Choctaw Vampire Hunters. I was really hoping they'd come riding in to save the day, or at least kill a few vampires. That's not a complaint about the film, I just wish I'd seen more of them, because they were awesome.

I also wish the film had made a bigger deal out of Stack's WW1 trench knife, because those things are bad ass, and look even cooler.

In the end, while it's fair to say that while Sinners may be a bit sloppy… I still loved it. It's one of my favorites of the year, and I would definitely recommend it.

Also, if you didn't see Ryan Coogler's Criterion Closet Picks, I would also recommend watching that, and the films that he mentions there too. He draws a line between Mann and Nolan that I never would've considered, and now it feels so obvious, I don't know how I ever missed it. He also mentions my wife's favorite film, Love & Basketball, as one of his favorites too, so that was vindicating for her. Anyway, there's some great picks there to check out when you have the time.