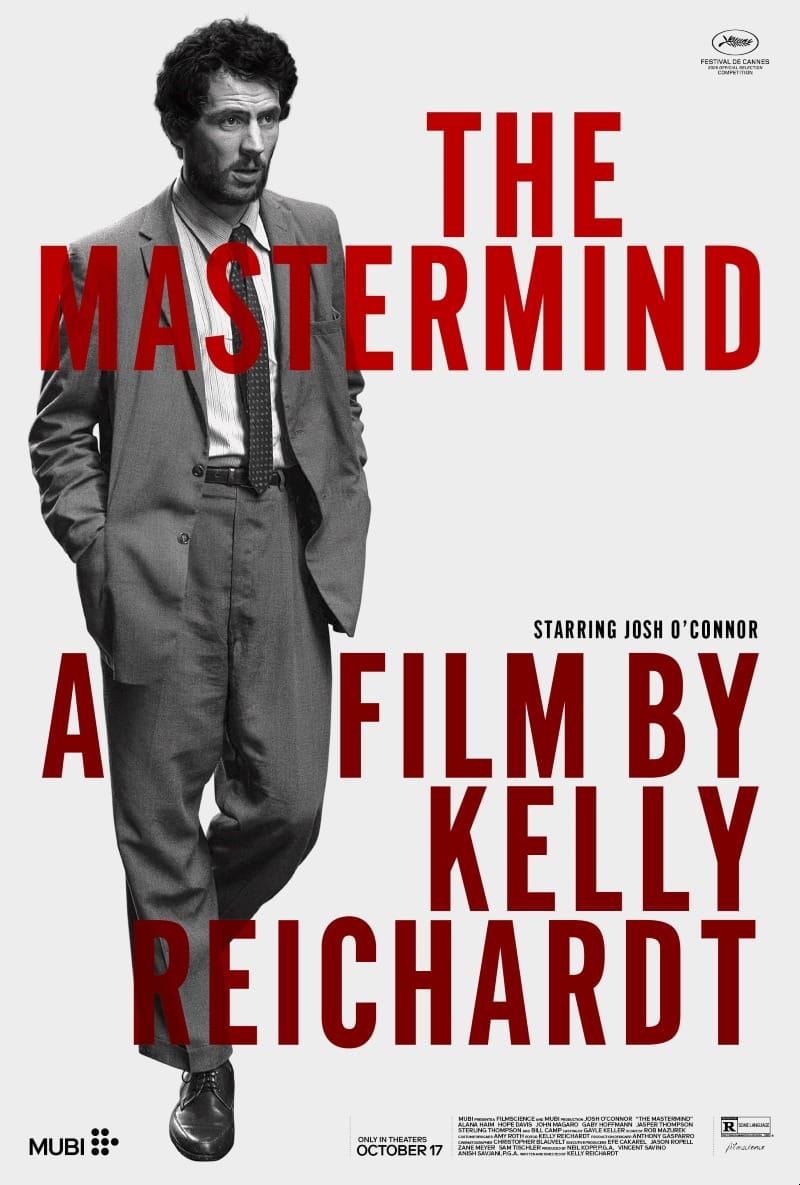

The Mastermind

The best laid plans…

In 1970, J.B. Mooney puts together a crew for a daylight museum heist, with the goal of stealing four paintings. When holding onto the art proves to be much more difficult than stealing it was, J.B. is forced to go on the run.

In 1970 Framingham, Massachusetts, an unemployed carpenter James Blaine "J.B." Mooney spends his days scheming to steal four Arthur Dove paintings from the local art museum, Tree Forms (1932), Willow Tree (1937), Tanks & Snowbanks (1938), and Yellow, Blue-Green and Brown (1941).

Using the last of his mother’s goodwill, J.B. borrows money to bankroll his heist under the pretense of using it to find work. Despite a few rough patches, after the original getaway driver backs out, forcing J.B. to drive, and the robbers pulling a gun on a student doing homework at the museum, and also beating up a security guard, in the end, they manage steal the paintings and get away.

J.B. Assumes the hard part is over, but moving the art afterwards is much harder. The heist is all over the news. Hiding the paintings, J.B. returns home to discover that the police and the FBI are questioning his family. They inform J.B. that one of the robbers was arrested while attempting to rob a bank, and that they named him as the mastermind of the heist. J.B. denies his involvement, using the threat of his father, a local judge, to temporarily hold the cops at bay. After they leave, he asks his furious wife Terri to take their sons Carl and Tommy to his parents' house, but Tommy refuses. With Terri and Carl out of the house, one of the other robbers calls J.B., pressing him for more money, forcing J.B. to take Tommy along to meet-up. But the meeting turns out to be a setup when some mob guys show up and abducts J.B. and force him to turn over the painting.

With the paintings and their promised payday gone, and with his role in the robbery made public, J.B. drops Tommy off with Terri and his parents, and goes into hiding with Fred and Maude, old friends from art school. While Fred is cool with it, Maude privately confronts him and tells him to leave. Fred suggests that J.B. hide out at his brother's Toronto hippy farm commune, but J.B. decides to go to Cleveland instead, and stay with some friends. But when he gets to Cleveland, he discovers that those friends left town the day before. Directionless, J.B. hitchhikes to Cincinnati. While hiding out in a cheap hotel, he learns that the paintings have been recovered and returned to the museum. He calls Terri, and tries to explain his actions, but she hangs up on him when he asks for money for a ticket to Toronto. Unable to afford the bus fare, J.B. steals an old lady’s purse and escapes into an anti-Vietnam War protest.

Unfortunately, the police violently break up the protest, and mistaking J.B. for a protestor, they throw him in the back of a police van and drive him to jail. The film ends with the cops briefly giggling and capering like happy idiots after trampling on people’s lives and rights.

I love a good heist film, and while I really enjoyed this film, let’s just be clear from the start… this is an anti-heist film heist film.

Like me, writer/director Kelly Reichardt has apparently had a long-running fascination with art thefts, and collects newspaper clippings about them. Similarly, a lot of her fascination seems to center on the idea how, in the 70s, it was so much easier to steal art, simply because it was just hanging on the wall, no differently from, say... in your grandmother's house. Also, like in the “greatest art heist of all time” the famous Gardner Museum heist—where one of the go-to things that tv and movies love to casually mention as an aside in order to illustrate how well-connected, and how much of a veteran criminal, the villain is, Rembrandt’s Christ in the Storm on the Sea of Galilee was stolen—security was usually just a bunch of disinterested drop-outs and half-asleep old men. And the craziest part to me about all the art that has been stolen and never recovered, is the way it just disappears. Presumably someone has it right now, just has it as their own, just for them. It's so crazily selfish, and such a weird idea to think about that, somewhere right now, in some random rich guy's house, Christ in the Storm on the Sea of Galilee is maybe just hanging over the toilet in one of their guest bathrooms...

Anyway, for this film, Reichardt was inspired by the 1972 robbery of the Worcester Museum in Massachusetts, where two Gauguins, a Picasso, and a Rembrandt were stolen. It was a clumsy, rushed heist where a gun was pulled on a teenage girl and a security guard was shot in the hip, and eventually, everyone involved was arrested and the paintings recovered. More of an art hiest footnote than a notable example, sure, but it's a good way of illustrating how casual and inexperienced and on-the-fly art heists seemed to be back in the day. Literally just... walk in, lift the painting off the wall, then run out, hopefully while everyone is standing there looking at each other, confused as to what's happening.

A classic smash and grab in a completely unprepared place. A part of me really loves that sudden infusion of chaos amongst an expectation of calm. It's a really nice metaphor for the allusion of safety, the falsehood that is a classist society.

It's almost an artistic performance piece itself.

But anyway...

If you’re looking for a traditional heist film, you won’t find it here. The Mastermind very much invokes the style and pacing of the New Hollywood films of the ‘70s, with its unconventional narratives, offbeat antiheroes, and laconic style of storytelling. Playing with genre expectations, Reichardt clearly isn’t very interested in focusing on the ins and outs of the heist as much as she is in the collapse of J.B.'s plans. As a result, it feels less like a heist film, and more like a metaphorical examination on a changing era in America, the point where “everything started to go wrong” as the counterculture of the ‘60s was smashed to pieces on the rocks of capitalism, and society seemed to collectively make the decision to allow itself to slide down into the muck of naked greed and excess that was the Me Decade. So, as a film, its clearly more of an exploration of the sinner than it is the sin, all of which is told through a series of slow extended sequences… spending the day casing the art museum… idly strolling through a forest… focusing on the heavy silence that hangs between conversation...

And all as a very jazzy score plays.

I really liked how the film also highlights how the ability to be an outlaw is a kind of privilege itself, as J.B. is basically just this mediocre every day guy, living in a comfortable suburb, who then completely blows up his life, and the lives of his wife and children, due to simple boredom, the disappointment of life not being what he wanted it to be, and a seething resentment towards his domineering asshole father. It also highlights how he does all this with barely a thought of what comes next too, just an absolute idle and privelged baby lashing out blindly, and then, as it seems he apparently always has, relying on the women in his life to pick up the pieces and keep him afloat. It's a very interesting additional commentary that really reflects on the general selfishness that is inherent to art heists too.

I really enjoyed what Reichardt has to say here, and how she said it.

Still, it’s important to state clearly… this film takes it time as it dwells on J.B. and his decisions. And this deliberate pacing has definitely upset people looking for a new Ocean’s Eleven or something… Ocean’s 1? One dipshit on Twitter described the film as “a complete nothing burger” and “nothing but jazz music,” which even if it wasn’t already apparent to you, as this person is still on Twitter, which is the preferred platform for Nazis, Russian bots, and Pedophiles, this is something that a stupid person would say, but still... it's also a common sentiment amongst your average movie-goer. So, fair warning, if you're the kind of viewer who demands fireworks and nothing but fireworks, then go watch something else.

Otherwise, this is Jack O’Connor’s show (recently of Wake Up Dead Man), and he brings a level of charisma and general air to his performance that is very similar to what Elliott Gould brought to films in the 70s—well, what he brought to all of his work, but in this particular case, specifically to his work in the 70s—and you could easily see him starring in this film. It’s a really great and natural performance, and between this and Wake Up Dead Man, I’ll be watching for more of O'Connor's work in the future.

Definitely worth checking out, especially if you like the idle arty stuff.