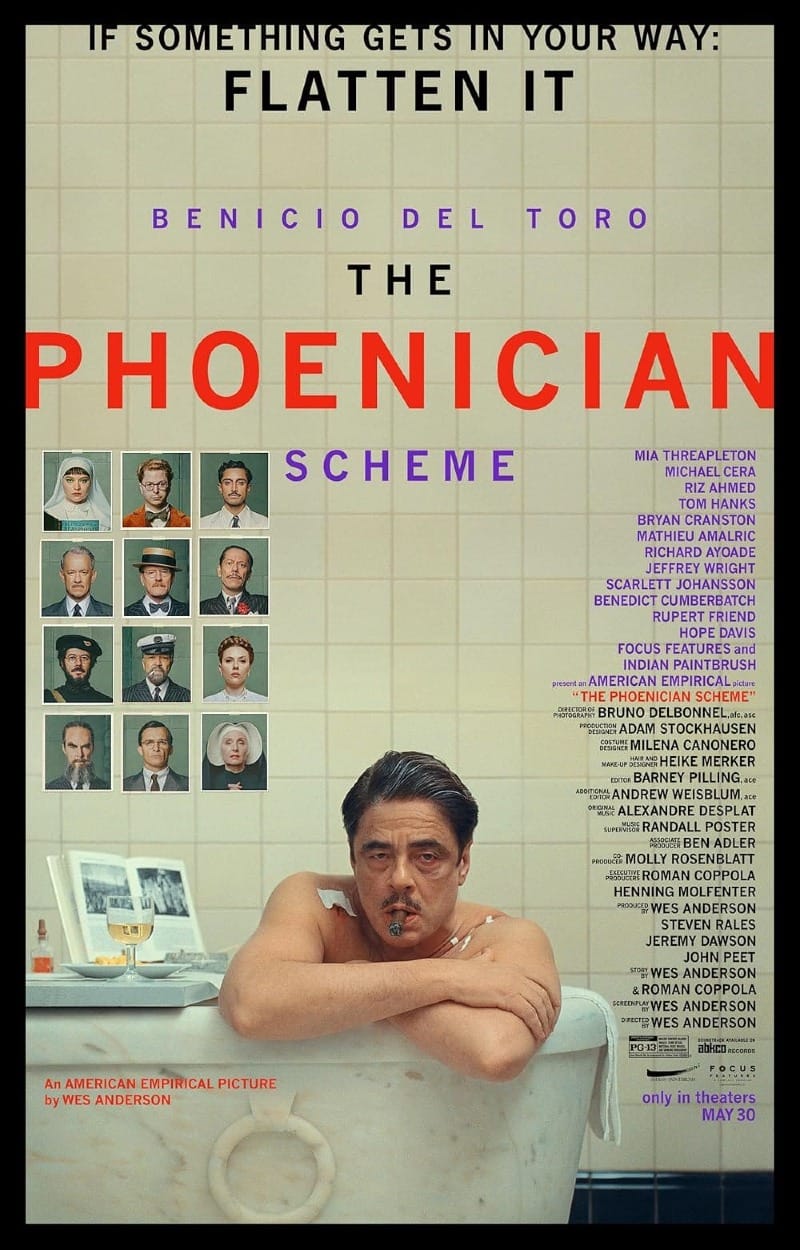

The Phoenician Scheme

“Please help yourself to a hand grenade”

After surviving yet another assassination attempt, wealthy businessman Anatole “Zsa-zsa” Korda decides to appoint his only daughter, Liesl, a nun, as sole heir to his expansive estate and many businesses. Embarking on an enterprise long in the making, along the way; Korda and Liesl become the target of scheming tycoons, foreign terrorists, and more very determined assassins.

If there's one constant in modern day cinema, if there's one thing that we can always rely on, it's that Wes Anderson is always Wes Anderson, and that, as time goes on, Wes Anderson can only ever become more specifically Wes Anderson, because Wes Anderson can only ever be Wes Anderson.

Growing up in the staid, deeply banal suburbs of northwestern Houston, Wes Anderson was born Wesley Wales Anderson, the middle child of three to Texas Ann (Burroughs) Anderson, an archaeologist turned real estate agent, and Melver Leonard Anderson, who worked in advertising and public relations. His parents would divorce when Wes Anderson was 8, an event that he described as the most crucial event of his childhood.It was at this time that he began writing plays and making super-8 movies.

After graduating with a degree in philosophy from the University of Texas, Wes Anderson screened his short film, Bottle Rocket, at Sundance in 1994. Even then, in the early days of his cinematic career, his preferred style, his favorite themes, his familiar litany of quirks and pcadillos, were all clearly evident. Over the years, this has not changed. If anything, his retro-aesthetic idiom of very deliberate and very nuanced offeringsof pastel colors, symmetrical compositions, droll repartee, vintage tchotchkes, and houndstooth stylings, has only grown more amplified.

Admittedly, there was a time where I found myself growing weary of Wes Anderson endlessly exploring his daddy issues in his very distinct, very neat, very exaggerated, very ridiculous, and very, very tightly controlled, little French New Wave-inspired dollhouse worlds. But now, here in perhaps his most emboldened aesthetical era, I think I’ve come around the far side of my weariness, and have landed once again back in his camp. As his pop art goes to unapologetic extremes, I find myself more and more enthralled, especially when he dives head-first into the rakish, mod styled world of turtleneck-clad spies, exotic locals, and daring adventures, like he's making some live-action Johnny Quest story....

Which is what we have here.

But all that aside, if there's one thing that has truly been made clear through Wes Anderson’s oeuvre, it's this… he truly is Max Fischer, isn’t he?

Anyway, on to the film...

Anatole “Zsa-zsa” Korda is international businessman.

A maverick in the fields of armaments and aviation, he is an accused profiteer, as well as a suspected tax evader, price-fixer, and briber, specializing in the mediation of clandestine trade agreements. He is hated by rival capitalistic nations around the world, is among the richest men in Europe, and has survived six plane crashes. In financial circles, he is known as Mr. 5%. He has had three wives, all of whom are dead, and ten children, nine sons and one daughter, Liesl, a novitiate nun.

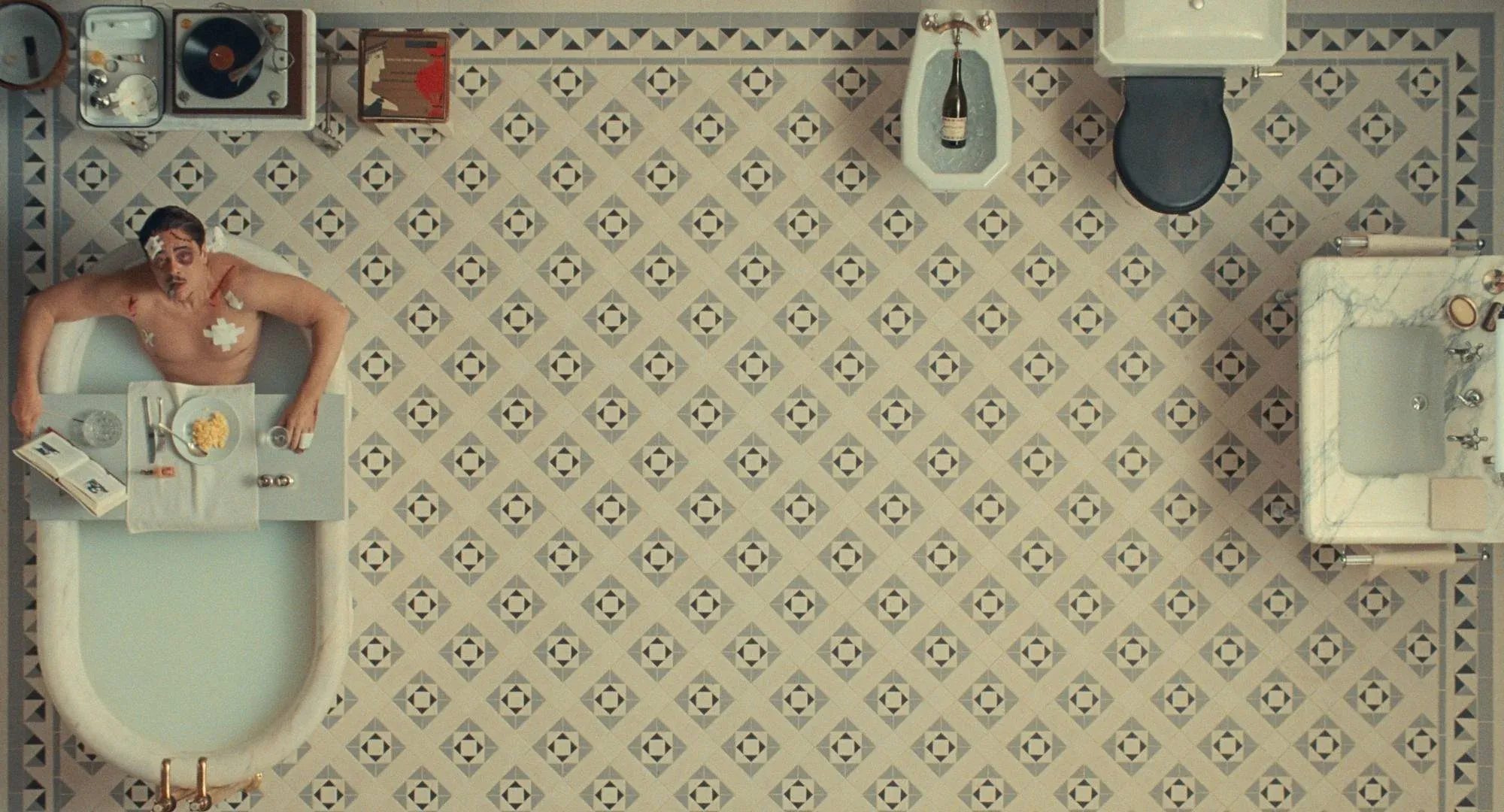

In the year of 1950, flying high above the High Balkan Flatlands in a private plane, at an altitude of 5,000 feet, Anatole "Zsa-Zsa" Korda narrowly survives yet another assassination attempt.

While lying unconscious in a cornfield, surrounded by the burning wreckage of his plane, Korda enters the afterlife, where a divine court waits to judge his worthiness to enter Heaven. He awakens, bloody, dirty, but still alive, and with the knowledge that certain things in his life must change.

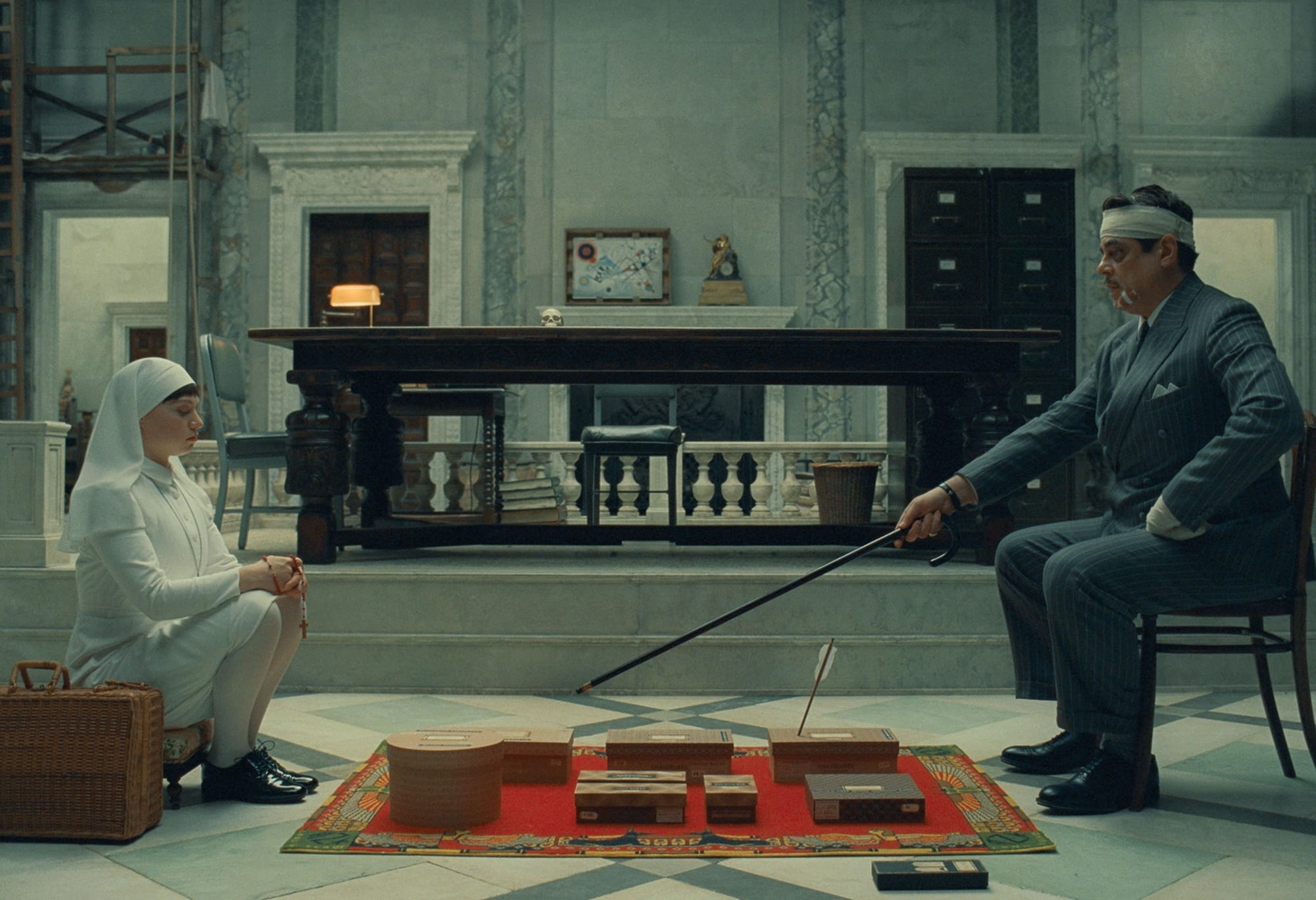

Knowing that he cannot run from his assassins forever, he decides to start by mending his relationship with his only daughter, Liesl, who is currently a novice nun. Korda decides to go about this by naming Liesl as his sole heir, who will take over his businesses upon his death, an offer which he explains to her in great detail. This will, of course, require her to quit the Church.

Obviously, they have a somewhat testy relationship, as the pair have been estranged for many years now, ever since Korda sent Liesl away to a convent at the age of five. On top of that, Korda is rumored to have murdered Liesl's mother, a rumor that Liesl is well aware of, but Korda denies. As a result, when coupled with his demand that she forswear her holy vows, Liesl is not immediately grateful or accepting of Korda's sudden and suprising offer.

Korda is willing to wait for her answer, and in the meantime, he takes her on a global tour of his many financial concerns, as a sudden shift in the cost of building materials means that Korda needs to drum up more financial backing or a plan he has had in the works for a very long time will not only fail to turn a profit, but will completely bankrupt him.

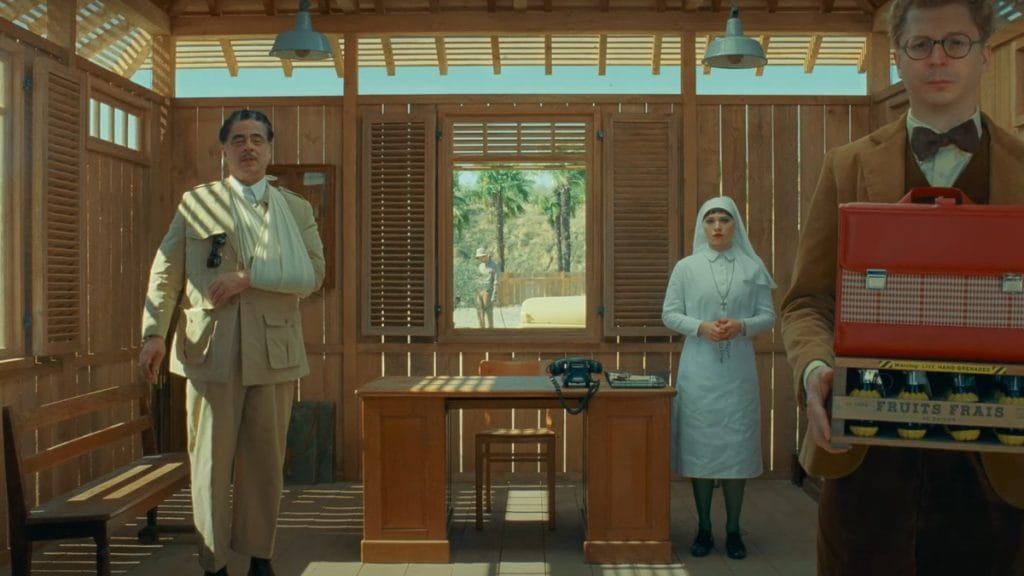

Also, Bjørn, a Norwegian entomologist, newly hired to act as a tutor to Korda's nine unruly sons, and now his freshly appointed administrative assistant, will be joining them on their travels.

You see, representatives of the world governments have been conspiring to stop Korda's unethical business practices. When Korda staked his fortune on this risky business scheme to overhaul the infrastructure of Phoenicia with slave labor, they were suddenly presented with an opportunity. Seizing their chance, they tasked the secret agency, Excalibur, to drive up the worldwide price of building materials, a move which forced Korda into the open, risking as assassin's bullet, in order to save his now floundering empire.

So, with Liesl and Bjørn in tow, Korda embarks on a globetrotting journey to swindle his investors into covering his sudden budget shortfall.

Without informing them of the change, Korda attempts to get the Californians, Leland and Reagan, to sign a contract increasing their financial contribution, but loses to them in a game of Horse. He attempts to blackmail the French nightclub owner Marseille Bob into increasing his share, but he is interupted when a gang of bandits posing as revolutionaries rob the club. He threatens to kill the East Coast businessman Marty in a suicide bombing in order to get more money, but that doesn't work out either. These underhanded dealings enrage his investors, but somehow Korda manages to wriggle his way out of each scenario.

Unfortunately, the investors only agree to cover 50% of the cost overrun.

During the trip, Liesl and Korda explore their odd relationship.

After taking a bullet for Marseille Bob, Korda meets Liesl's mother in the afterlife and she tells him that he is not Liesl's father. Korda realizes that all he had to offer his family was money, not love. In addition, during his confrontation with Marty, a guilt-ridden Korda admits all of this to Liesl, and admits that he had known years ago that Liesl's mother was having an affair with his estranged half-brother Nubar, and that, to get back at her, he faked a story that she was also having an affair with Nubar's assistant, which prompted Nubar to kill Liesl's mother in a jealous rage. To make matters worse, he then admits to Liesl that despite all of this, he still does business with Nubar, who is also an investor in Korda's Phoenician scheme. Liesl is outraged to learn of her father's amorality, but she agrees to continue helping him so that she can send Nubar to jail.

In a last-ditch attempt to avoid asking Nubar for help, Korda offers to marry his cousin Hilda, an heiress to the Korda armaments fortune. She accepts his proposal but refuses to increase her investment. This is not the outcome Korda was aiming for, and now he has no other choice then to turn to Nubar, a man that Korda does not consider human, but to be more... biblical.

On the flight back home, saboteurs destroy Korda's plane.

The wreckage reveals that Bjorn is actually a spy working for Excalibur's consortium, and that he isn't Norwegian either, but American. However, as he has since fallen in love with Liesl, he agrees to switch sides. Unfortunately for Korda and Bjorn both, Liesl has decided to return to the Church. Unfortunately for Liesl, her mother superior dismisses her from the order, explaining, what with her little pipe and her fancy rosery, that she is simply too materialistic for the religious life.

Her future thus decided, Liesl joins Korda and Bjorn at the Desert Oasis Palace hotel, where Korda's investors have gathered for a presentation of the Phoenician Scheme. But first, Korda finally meets with Nubar. It is then that Nubar takes the opportunity to announces that not only he is withdrawing his entire investment, and that he is not Liesl's real father, he also reveals that he was the one who has been trying to kill Korda this whole time, mostly in an attempt to keep things "sporting" between the two half-brothers.

Nubar then tries to kill Korda in a brawl, but Korda defeats him.

It is at this point that Korda decides to pay his workers, and to then throw his entire fortune into completing the Phoenician scheme, believing that finishing a worthy project will give his life meaning. Thus bankrupted, Liesl accepts Korda as her father. Hilda then has her brief marriage to Korda annulled and gives back her wedding ring, which Korda then loans to Bjorn, who then proposes to Liesl, who accepts. They all retire to the simpler life of running a small bistro, where Liesl and Korda end each day playing cards together as a family.

So...

A little gorier at times than in his usual fare maybe, but featuring all the usual faces, The Phoenician Scheme is definitely one of Wes Anderson's goofier films, and feels much more narratively focused than his last outing. But while this one probably won't be anyone's favorite Wes Anderson movie, it's pretty charming and easy to like overall.

As goofy as The Phoenician Scheme is, written by Wes Anderson and Roman Coppola, with its farcical central scheme involving massive construction projects in a fictional possibly Middle Eastern nation called Phoenicia, the main question here is a little deeper, concerning itself with how our actions in life determine how we’ll be judged after our death. While this is a subject that is perhaps never too far from the minds of mortal men, it's a pretty topical consideration these days in the wake of some recent high-profile deaths. It's also something that will definitely come up again, sooner rather than later, due to the plethora of... shall we say... morally and ethically dubious, not to mention exceedingly unpopular, power-mongers who are in charge of this gerontocracy-hobbled society, as they are all right now standing with one foot held out of their own open graves and wobbling unsteadily. And while it's fair to question whether or not this judgement may come from whatever version of the afterlife that some random zealot believes in, it will definitely come from those of us who are left behind to note the passing. So, it's a worthy question for everyone to consider, right?

Are you living your life in such a way that possibly millions of people won't celebrate your passing?

This film also interrogates the structures of power directly, which I like, and this is mostly done through Mia Threapleton, who plays Leisl, who acts as the conduit of morality and logic, replying with a relentless barrage of simple and straightforward questions in the face of her father’s constant stream of lies and evasions. Leisl is a deft foil to Benicio del Toro's Korda, a cold and detached capitalist monster, driven by naked greed and a need to dominate, who murders and enslaves as casually as he might order dinner. It's only when Korda somehow survives multiple attempts on his life, often leaving him injured and bloody and haunted by brief glimpses of the divine tribunals awaiting him in the Great Beyond, that he finally embraces redemption, and only then, as a result, does he find happiness and fulfillment.

Basically, what the film says here is that it's only once you stop allowing yourself to sacrifice others, those less fortunate than you, those who are more marginalized in society, and all for your own enrichment, comfort, and convenience, can you truly be a human being with a soul.

This whole story is an obvious farce, all while being a little loose and self-indulgent, sure, but it's also a redemption story of sorts, in its way asking that you consider that old saw... "For what shall it profit a man, if he shall gain the whole world, but lose his soul?" This is, of course, a lesson that will mostly fall on deaf ears amongst the bigots and assholes out there who are currently destroying this country and the world, the people who definitely need to hear it the most, but alas, are also highly unlikely to ever even watch a film like this, but hey...

At least the film is trying to send the message.

Anyway, like I said, all the usual faces turn up here–so much so that it almost seems to highlight Jason Schwartzman's absence–along with a few notably new ones, all of them delivering performances in the same comic register you usually find in a Wes Anderson film (I particularly enjoyed Hanks and Cranston as the ruthless Californian investors). But it is this expected delivery that makes Michael Cera's performance all the more noteworthy. He is clearly having a great time, turning in a deceptively complex performance that is really fun to watch. In fact, he not only gives the best performance in the film, but maybe the best one of his entire career. He just seems right at home in Wes Anderson's weird world. That this is the first time Cera and Anderson have worked together amazes me. As someone commented online, Wes Anderson must've felt like a caveman discovering fire when he cast Michael Cera.

So, if you were maybe hesitating to watch this one, which I get, because sometimes Wes Anderson's whole thing can be too much of a thing, I'd say that Michael Cera makes it worth checking out.

Watching Wes Anderson play with religious imagery as a morality play for the potential repercussions of living a corrupt life feels very familiar to me, relatable, like it might be a natural consideration of someone who is getting older, and watching the downward slide of a crumbling empire, to spend some time with turning over in their head.

Maybe that's why you can kind of feel Anderson backing away from these ideas a bit. Maybe the reflection of the political and personal corruption in this modern world is simply too harsh, and that staring into that abyss for too long makes it to hard for him to make a silly little comedy at the same time.

That also feels very relatable.

And maybe that's cowardice, I don't know. Maybe a better version of this film almost existed as a story that skewers powerful people out there, casually gifting one another with grenades, all while bringing a myriad of childen into this world for the purposes of their own legacy, only to turn away from them when they don't fit in the ways they were intended too, maybe we almost had that, but Anderson flinched. Maybe. Like I said, I don't know. Doesn't matter now, I guess. In the end, like most things these days, the best we can really hope anymore for is a fun albeit momentary distraction as the world burns.

Still, there's some hope here, a little bit of steeel, as Wes Anderson seems to consider what it means to be both a good person and also a successful person, a wealthy person, and how those who have lost sight of their humanity can possibly find it once again, but only if they learn that it's simple things in life that matter, that others matter just as much as you, and that, in the end, doing good in this world is the key.

So, The Phoenician Scheme is fun, it's good looking, it's almost actually saying something, but mostly, these half-dozen shoeboxes that the plot is neatly divided up into all end up mostly seeming like little compartments where Anderson and Coppola can showcase the things that they like. And that's fine, I certainly don't mind a little artistic self-indulgence, especially now, but... Is this film better than Rushmore? Is it better than Royal Tennebaums? Is it better than Life Aquatic? Is it better than Moonrise Kingdom? Is it better than The French Dispatch?

No.

It's not reinventing the kind of wheel that one can reasonably expect from a Wes Anderson film either. It trods a lot of the same ground, and circles the usual Daddy Issues too, just like most of Wes Anderson's films do. And, much like Asteroid City, it’s definitely fair to say that this film is overall more interested in style than it is in substance, but... let's be honest here, at this point in Wes Anderson's career, you’re either in or you're out. And you should really acknowledge that before you consider whether or not you're going to check out this one.

I read recently that Wes Anderson has a billionaire patron who is a huge fan of what he does. This would explain why Anderson's distinct vision and voice has gotten so much more pointedly and unapolegetically niche ever since Moonrise Kingdom in 2012. Apparently, the billionaire Steven Rales has a net worth of 8.9 billion dollars, all made with old fashioned "greed is good" 1980s private equity, diversified investments, and hostile takeovers, but he is also reportedly a HUGE cinephile. After opening Indian Paintbrush Production Company in 2006, he's been working with Anderson, funding his films ever since.

A real modern day Medici, I guess.

I mean, he's probably a piece of shit, of course, no one can become a billionaire without being a fundamentally, and perhaps irredeemably, bad person, but I do wish that more of these assholes would be patrons of the art and/or build things, instead of poisoning the world with their egos, their garbage AIs, their insatiable need to be liked, and their bitterness over their broken penises. But, much like everything else good in this craptastic asshole world, that is way too much to ask for apparently.

Anyway, The Phoenician Scheme was fun. It's worth checking out, if you like Wes Anderson's stuff.