The Princess Warrior

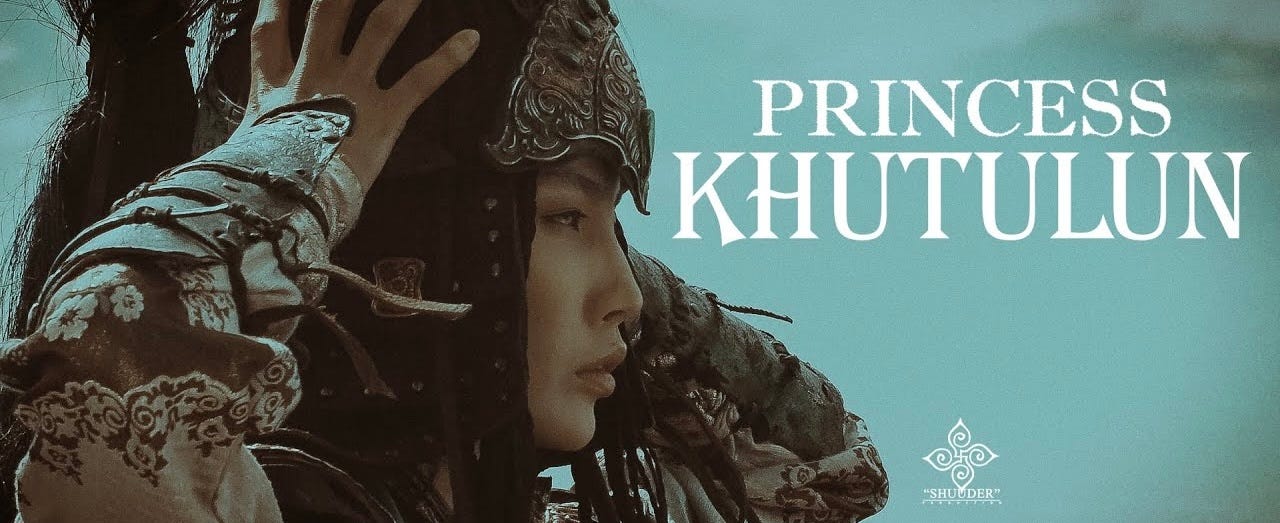

Also known as Khutulun Princess

Descended from Genghis Khan, skilled in all forms of military combat, Princess Khutulun is one of the fiercest warriors in the Mongol Empire. However, despite her many talents on the battlefield, Khutulun is still expected to marry and become a dutiful wife. But after her father is ambushed by assassins sent by his sworn enemy, and the Golden Sutra is stolen, Khutulun and a small band of warriors set out on an epic journey to retrieve the sacred text and restore peace to their homeland.

Khutulun was born about 1260, the great-great granddaughter of Genghis Khan.

By 1280, she was a well-known warrior. Reputedly a very large and powerfully built woman, she used her size and strength to excel at horsemanship and archery, the kind of warfare favored by Mongolians. She was especially well known for dominating the Mongolian style of wrestling, a sport which is more like Ultimate Fighting than it is Greco-Roman, where legend says no one ever defeated her.

Of all her father’s children, Khutulun was his favorite. She is the one from whom he most sought advice and political support from. Her strength and ability aided him in becoming one of the most powerful rulers of Central Asia, where he reigned from western Mongolia to the river Oxus, and from the Central Siberian Plateau in the north, to India in the south. According to some, he even tried to name Khutulun as his successor to the khanate before he died in 1301.

Surprise, surprise, her male relatives objected to this.

Legend says that Khutulun was reluctant to marry, and after putting it off as long as she could, she declared that a public competition would be held for her hand, with an entry fee wager of 100 horses. According to Marco Polo, at the time of his encounter with the princess, she had 10,000 horses of her own, and had yet to be defeated by any warrior, be they Mongolian or foreign.

Khutulun eventually did get married, but the texts do not disclose his name. Some chronicles say her husband was the man who failed to assassinate her father and was then taken prisoner. Others refer to him as one of her father’s companion. Rashad al-Din claims Khutulun fell in love with Ghazan, the Mongol ruler in Persia. Whoever it was, it seems more widely accepted that she eventually married to dissuade rumors, rumors that had mostly likely been started by her father’s enemies, that the reason she would not marry was because she was involved in an incestuous with her father.

She died in 1306.

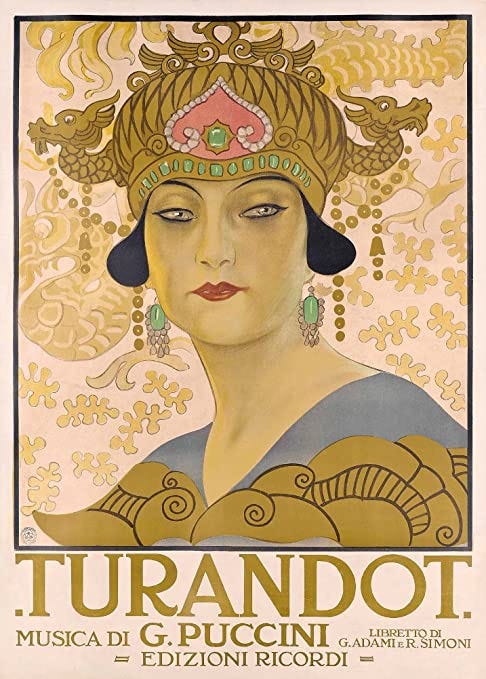

Although mentioned in a variety of Muslim sources, as well as in the accounts of Marco Polo, Khutulun almost unknown in the West until 1710, and when she was, it was not as the wrestling champion and warrior princess that she was. François Pétis de La Croix published a book of Asian cultural tales and fables, one of which featured Khutulun. In his adaptation, she was known Turandot, meaning “Turkish Daughter,” and instead of challenging her suitors in wrestling, she would pose three riddles, and instead of wagering horses, the suitor had to forfeit his life if he answered incorrectly. In the mid 1700s, Italian playwright Carlo Gozzi made her story about of a “tigerish woman” of “unrelenting pride.” Italian composer Giacomo Puccini died finishing his opera Turandot in 1924, which was the story of how the princess would reject any man’s offer of marriage, if she deemed him as being inferior to her.

This time, the story of Khutulun is called The Princess Warrior, and the story leans a little bit closer to history.

A little bit…

Directed by S. Baasanjargal and Shuudertsetseg Baatarsuren, and written by Shuudertsetseg Baatarsuren and Boldkhuyag Damdinsuren, Princess Khutulun’s story is a more action movie-like version this time. Although, when it comes to discussing her lineage, they seem to have cut out a couple of “greats,” implying that she is a more direct descendant of Genghis Khan.

Anyway, it goes something like this…

From a young age, Khutulun has shown great prowess in combat, and, alongside her father, she has led her people to many victories. Despite this, she still is expected to marry and live a domesticated life.

While journeying to meet her betrothed, a prince in a neighboring clan, they are attacked in the night by assassins, and the sacred Golden Sutra is stolen by none other than Khubilai—grandson of Genghis Khan, as well as founder and first emperor of the Mongol-led Yuan dynasty of China. Khubilai, also known as Kublai Khan, is someone who, along with the civilization of the Chinese Court, had long been not just her and her father’s enemy, but the enemy of Mongolia’s traditional nomadic cultural lifestyle too. Khutulun resolves to retrieve the stolen manuscript, and to set things right in her homeland, putting her on a path of epic deeds and epic glory…

She isn’t portrayed as all that big or physically intimidating though…

But the most shocking thing about The Princess Warrior is not how short the actress (Tsedoo Munkhbat) playing Princess Khulutun is, but how short the film is. At only 86 minutes, it flies by, which is an interesting choice given how it’s a film concerned with events of historical upheaval, great battles, and a bunch of political intrigue, not to mention a little bit of magic too. But yeah, it’s less than an hour and a half long, so much like the Mongol warriors of old, as soon as The Princess Warrior starts, it’s galloping at full speed.

The appropriateness of longer or shorter run-times is a constantly argued topic among filmheads, with weirdo zealots on both sides, people who claim that any film longer than 90 minutes is wasting time, and any film shorter than two hours will have an underdeveloped story and characters. Few seem willing to admit that the argument itself is a huge waste of time, because it’s stupid and pointless, as whether or not a shorter or longer runtime works better is totally dependent upon what the film is specifically about, and how the story is specifically being told.

But that aside…

On one hand, sure, shorter stories can be leaner, more focused in the way they tell their tale, and best of all, there’s momentum. On the other, a longer story allows you to get to know the characters and the world, to go deeper into the story. Plus, often times too much momentum can lend a story a feeling of running headlong downhill, making it difficult to see any of details or smaller important bits as the story’s world turns into a blur. Like I’ve said before, The Force Awakens is a great example of film with the wrong run-time, being that it should’ve been longer, as it’s a film that cut out too much of its narrative connective tissue, all in favor of more momentum, which ended up giving us a story that didn’t have enough meat on its bones.

This is The Pincess Warrior’s main issue.

Here, a lot of who these characters are, and why they’re doing what they’re doing is either vaguely mentioned, or too quickly. It just feels hurried, and too broad. Plus, I feel like Khutulun’s band of warrior companions, men known as Hawk, Eagle, Wolf, and Bear, would’ve maybe stood out more in the story if each one of them had been given a signature weapon to carry.

Yes, I’m aware that I’m basically complaining that these guys aren’t depicted more like the Ninja Turtles are in this film, but this was my main takeaway after watching and trying unsuccessfully to keep Khutulun’s little back-up band straight.

Otherwise, besides the stunning costumes and cinematography, mostly due the incredible vistas of Mongolia, I liked the way they addressed the princess’s desire to avoid marriage and to be her own person. The moment where she questions why she was even born a human being if she’s not free to live her own life was really direct, and really well done, without insinuating hidden gender or sexual issues, just the desire to live her own life.

I liked that.

On the downside, besides feeling too hurried overall, for an action film, the fight choreography left a bit to be desired. Those scenes weren’t shot all that interestingly either. It was mostly just a jumble of people pushing each other, all of whom maybe could’ve used a little more stage-fight training. Also, for some reason, the filmmakers switched the title for the wider release, and it’s a much worse version. Okay, maybe they did it because Khutulun is not the most familiar word, as it was originally called Khutulun Princess, but The Princess Warrior is too generic, and too easily confused with any number of other films, The Princess and the Warrior, or Warrior Princess, or The Princess Blade even, and that’s without even mentioning another film that is actually called Princess Warrior (no “the”).

Total fumble.

In the end, while The Princess Warrior is probably not good enough for me to recommend you actively seeking out, and will definitely never break out of deep obscurity, or even build a real cult following, as always, it was kind of interesting to see another country make a game attempt at a Hollywood style action film, filtered through their own cultural lens, an effort which, for the most part, they succeeded.

For the most part…